What Does It Mean to Be Reformed? Covenantal, Confessional, Calvinistic

- Nino Marques de Sá

- Jan 6

- 3 min read

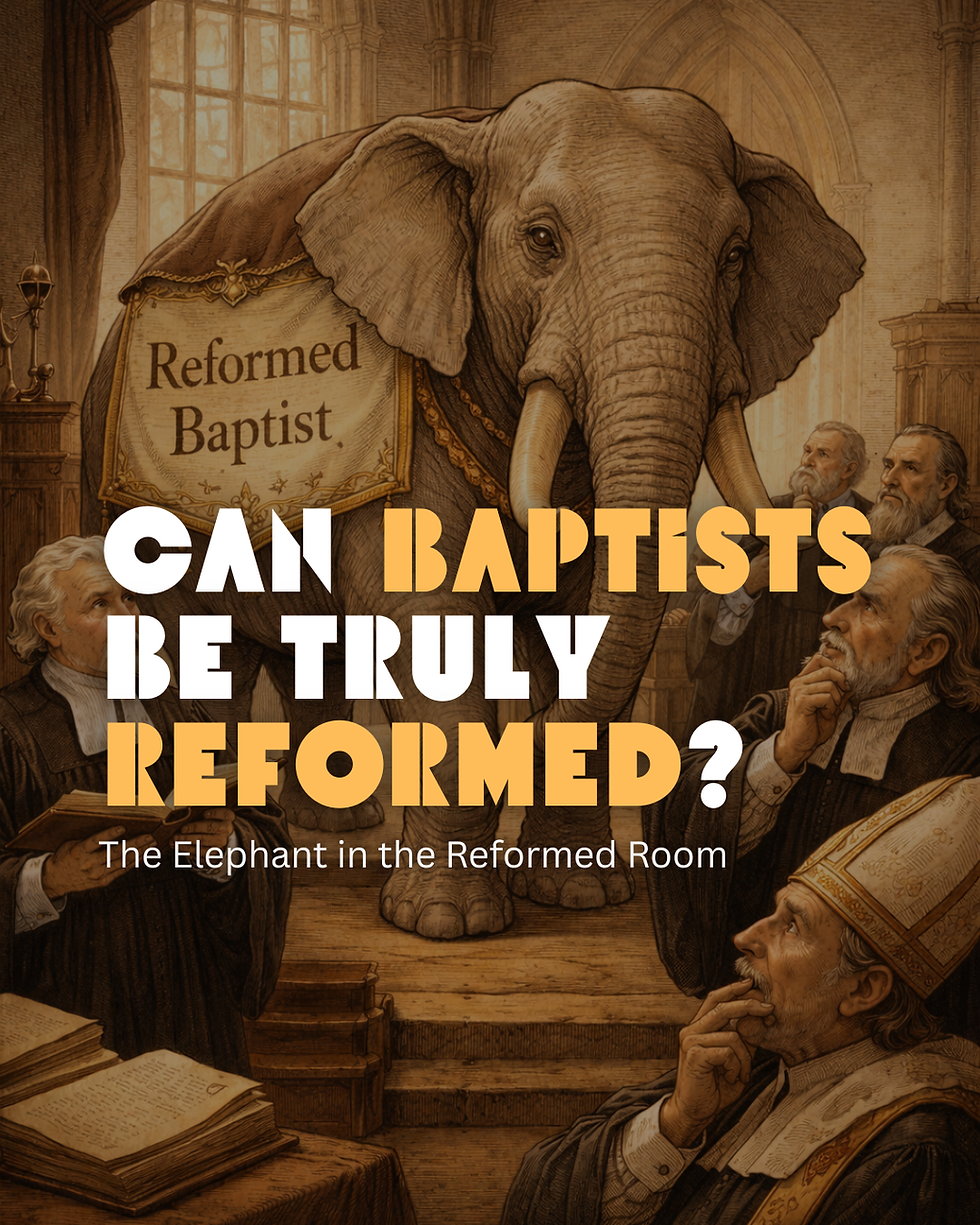

In the last few decades, the term Reformed has become increasingly popular among evangelical Christians. At the same time, there is significant confusion around what the word actually means. My goal here is not to defend a tribe, but to explain a theological identity.

For some, Reformed means traditional, rigid, or overly intellectual. For others, it simply means Calvinist. While these characteristics may often be found in Reformed churches, they do not tell the whole story.

Historically, to be Reformed is to hold together three inseparable commitments: Covenantal, Confessional, and Calvinistic. Let me briefly walk through each of these.

1. Covenantal: Reading the Bible as One Redemptive Story

In Reformed theology, covenants are the backbone of the biblical story. God relates to His people throughout the ages through covenants—not through disconnected commands or different ways of salvation in different eras.

The Bible is one unified story of redemption. There is one people of God throughout history, all saved in the same way: by grace through faith in the promises of God, given within the context of covenants. When we read Scripture this way, we see real continuity between the Old and New Testaments.

This matters because it shapes how we read Scripture and has real implications for how we understand the gospel, the church, the sacraments, and what Jesus accomplished through His life, death, and resurrection.

2. Confessional: A Faith That Is Public, Defined, and Guarded

Reformed churches confess their faith openly and historically. In fact, every church has a confession of faith; the real question is whether that confession is public, clearly defined, and historically tested.

A confession is simply a summary of biblical doctrine. It does not replace Scripture, but it helps a local church clearly articulate what it believes and teaches.

In many evangelical churches today, theological commitments exist but are not clearly expressed anywhere. This leaves churches vulnerable to internal and external influences, often without anyone noticing that theology is changing. Without a clear confession, there is little doctrinal clarity and no strong sense of historical continuity. As Christians, we should want to hold to what the church has believed throughout history.

Of course, not all confessions are Reformed confessions. To be a Reformed church, one must hold to a confession that arises from the Reformed branch of the Protestant Reformation. While Lutherans and Anglicans are part of the broader Reformation, they are not historically considered Reformed. Reformed confessions include the Westminster Confession, the Savoy Declaration, the 1689 Baptist Confession, and the Belgic Confession, among others. These come from the Calvinistic stream of the Reformation, which leads us to the final “C.”

3. Calvinistic: Salvation as the Work of a Sovereign God

You can be a Calvinist without being Reformed, but you cannot be Reformed without being a Calvinist. Some well-known Calvinist preachers and churches are not Reformed because they are neither confessional nor covenantal in their framework for reading Scripture.

As Reformed Calvinists, we have a prior commitment to historic confessions. Our understanding of Calvinism is therefore shaped by the Canons of Dort. When Calvinism is detached from confessional boundaries, people often develop their own versions of it—sometimes overlapping with historic Calvinism, but often differing in tone, clarity, and biblical grounding.

Calvinism, historically known as the doctrines of grace, affirms human inability because of sin, God’s sovereign election, Christ’s definite and effective atonement, the Spirit’s irresistible work, and the perseverance of the saints.

Contrary to common misconceptions, Calvinism is not fatalism. It does not eliminate human responsibility, nor does it undermine evangelism. Properly understood, Calvinism teaches that salvation from beginning to end is the work of God’s grace. God saves sinners, not those who make themselves savable. This gives Reformed churches a firm foundation for assurance, humility, and worship.

Why All Three Matter Together

In a future article, I will explain in more detail why these three commitments must be held together. For now, it is enough to note that each one, when isolated, creates problems:

Covenant theology without Calvinism can drift into moralism.

Calvinism without covenant becomes abstract and can undermine assurance.

Confessionalism without the other two can harden into rigidity.

Reformed theology is a system, not a slogan. To be Reformed is not merely to affirm certain doctrines, but to embrace a way of life. It shapes how we read the Bible, how we worship, how we evangelize, and how we understand family, work, and the Christian life as a whole. While Reformed theology shares the core of Christianity with other traditions, it remains distinct, just as Lutheranism, Pentecostalism, and other systems are distinct in their own ways.

May God give us the grace to understand His Word rightly, the humility to speak it with love, and the power to live holy lives as He designed.

Nino Marques

Comments